Two alleged sightings of the elusive moose in Fiordland has begged the age-old question — is it still out there? Mary Williams speaks to the yay-sayers, nay-sayers and maybe-sayers.

IT is a question of what we hold deer.

Two Fiordland moose sightings, both this year, by groups of Canadian and United States trampers on the Kepler track, were treated as a yeah-nah by the Department of Conservation (Doc).

Te Anau Doc manager John Lucas said he had to check that one sighting, which landed on his desk on April Fool’s Day, wasn’t a prank.

They were most likely ‘‘deer or possibly a red/ wapiti cross that has been mistaken for moose.’’

But this is not a hunt for the proverbial Big Foot.

Ten Canadian moose were released at Dusky Sound in 1910, after a tortuous journey from their colder homeland.

They bred but by all accounts never got much of a hoof-hold and, ‘‘it is believed they are now extinct’’, Mr Lucas said.

Belief and extinct are dangerous words to bandy around in Fiordland.

Te Anau residents celebrate Dr Geoffrey Orbell, the man who tracked the ‘‘extinct’’ flightless takahe in 1948 and found a few of the surviving birds in the mountains immediately opposite the township.

Four years later, the last definitive Fiordland moose photos were taken, so anyone claiming they are still out there in the 21st century must steel themselves for a storm of scorn from social media and some deer hunters.

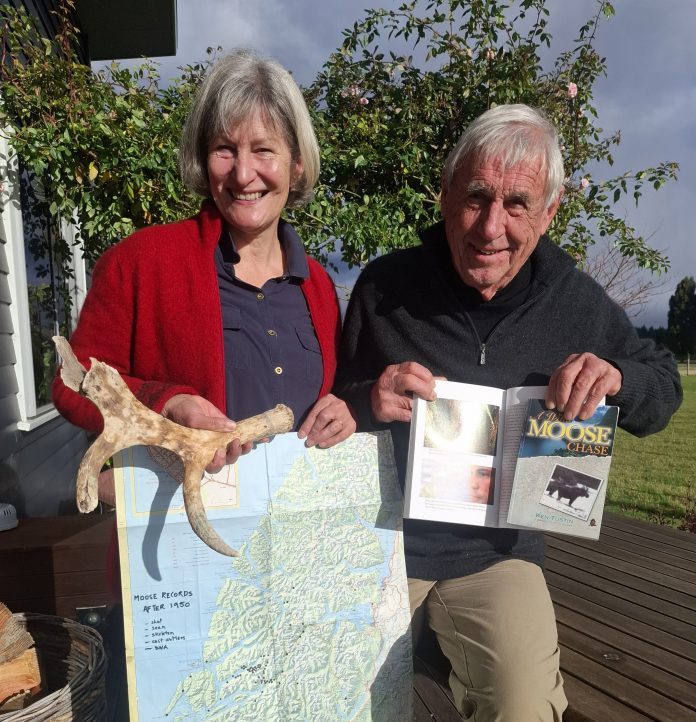

At the eye of the storm is the affable, long-married, Te Anau couple Ken and Marg Tustin, who have spent years — yes, years, often in month-long stint — living under canvas in a remote corner of Fiordland National Park, looking for moose.

They have used scientific approaches, have a hopeful, funloving attitude as well as some compelling evidence, and are convinced that a remnant moose population is still, probably, a yeah-nah-yeah.

Mr Tustin — a trained biologist, helicopter pilot and now in his 80th year — is riled at Doc’s recent negative reactions.

‘‘It is absolutely astounding,’’ he says.

He is responding by inviting people to report their sightings or other evidence to him and has set up an initiative called Moose Log NZ to help people do just that.

‘‘It amazes me that they [Doc] were so disrespectful, dismissing the sightings so out-of-hand, telling them ‘what they saw’.

‘‘We are talking about Fiordland mega-fauna here, not stick insects.’’

If a moose walks through the forest, but there is no-one there to snap its photo, is it still a moose?

According to Doc’s Mr Lucas, no. He demands ‘‘photographic proof’’.

Mr Tustin, who has been looking for moose since the 1970s, points out that Fiordland is 1.25 million hectares.

Moose are huge, look different from deer but the chance of snapping a photo is slim.

Only a few may be left, and if they are out there, they are solitary and likely on the move, looking for a limited supply of edible leaves.

They don’t hang out in clearings because, unlike deer, they are neither grass-grazers nor are they sun-seekers.

They are meant to have a different diet in a colder clime.

However, the two recent sightings by two groups — certain about their ability to ID moose, including a vet, and not colluding — have a ring of truth.

Antoine Beauchamp, from Quebec, explains why his group of three didn’t snap a pic. Their phones were in their backpacks because they were on their final day trudging the track and focused on making it to the carpark not nature photography.

‘‘Everyone wants to see something with their eyes but even then might call it false.

We have seen the comments on Facebook saying ‘Why didn’t they take a picture?’ but our phones were not in our hands.

We noticed the animal, started talking about it, it crossed the track so we got a good look, then it disappeared into the forest.’’

He admits there is always a chance they could be wrong but ‘‘it is important, first, to be kind and understanding, especially in a situation like this. I understand the takahe’s story so it is only fair to be open to the possibility of moose.’’

Mr Beauchamp then rattled off the moose characteristics they saw — wide flat antlers, wide nose, very long legs, brown body. If it looks like a moose, it’s a moose, he thinks.

During 1951-52 three moose were shot by hunters, one of them at a small lake called Moose Lake.

It is a wild, forested, moody spot fed by Herrick Creek and emptying into the southern edge of Wet Jacket Arm, not very far from the 1910 moose release site.

Moose Lake is named thanks to Mr Tustin.

He persuaded the NZ Geographic Board to name it because two moose had been shot there, the other in 1934.

In 1952, a moose was also photographed standing in the lake.

The area around Herrick Creek and Moose Lake has been the primary focus for much of the studies by the Tustins and Mr Tustin describes his time there with Mrs Tustin as ‘‘demanding, primeval but we thrived on it — lucky us!’’

They concluded that ‘‘browse sites’’ — where bush and tree stems have been broken and munched higher than a deer or wapiti could likely reach — demonstrated seasonal moose movements.

They installed self-triggering cameras, that snapped 1500 red deer and, in 1995, ‘‘one probable female moose’’, captured on a blotchy picture, taken from a video frame.

Max Quinn, 75, is a natural history film-maker and was making a film about the Tustins at the time.

‘‘We saw social groups of deer but the time we filmed that solitary, dark animal was the only time we saw it — a one-off, indicative of moose’’.

In 2000, two hunters found large hoof prints and some unusually-long, snagged animal hair at Shark Cove in Dusky Sound.

It was sent to Invermay Agricultural Centre for mitochondrial DNA testing and came back 98% moose.

Jamie Ward works at Otago Fish and Game now, but was a lab technician at Invermay.

It was ‘‘dumb luck’’, he says, that the sample was less than a few days old and therefore still testable.

Mr Ward is aware humans share 98% of our DNA with chimpanzees, but the hair follicles came back with lower matches for deer or wapiti that ‘‘weren’t even close’’.

He joined forces with Mr Tustin to co-author a paper, still available on ResearchGate.

In 2002, the Tustins also found a hair clump, on the northern coast of Wet Jacket Arm opposite Oke Island, and sent it to a forensic lab at Trent University in Ontario.

It came back moose positive.

Other samples they sent were found, predictably, to be deer.

In 2011, the clothing retailer Hallenstein Brothers offered a bounty of $100,000 for a photo, saying it was time to ‘‘help Ken Tustin out’’ but ended the offer six weeks later.

Since the DNA results, there has been nothing so helpful to prove moose, but in 2020, Ben Young, a young helicopter pilot at Southern Lakes Helicopters, said he saw one from the sky.

He has worked as a hunting guide in northern Canada and said he was sure.

The Tustins think there may have been other sightings not reported to Doc, because people fear ridicule.

In a few weeks, there is another chance of moose news.

The Tustins will be studying pictures from cameras they have placed in the Seaforth Valley, which leads from Dusky Sound towards the northeast, in the direction of the Kepler track.

Last year, Mr Tustin collected faeces from the valley in a place that he says was moose-browsed.

He sent it to be DNA tested by Massey University but, sadly, it had degraded too much.

Dr Nick Sneddon, who did the checks, explains that only the mucus on faeces can be tested and it degrades fast.

Meanwhile, the hunting community are variably likely to start collecting poo or holding cellphones at the ready.

David Veitch, experienced hunter and president of the Southern Lakes Deer Stalkers Association, is an ardent naysayer and uses an age-old argument.

He has walked ‘‘thousands of kilometres’’ through Fiordland bush and never seen one with his own eyes.

‘‘It is people not identifying what they are looking at, simple as that.’’

Owner of Te Anau hunting shop Fiordland Frontier Stephen Dobson is less damning.

He would love to be proven wrong about moose extinction but preferably not with a carcass as evidence.

‘‘Nobody wants to be that person who proves it by shooting the last one.’’

Roy Sloan, spokesman for the Wapiti Foundation, which is calling for wapiti to be protected as a Herd of Special Interest, is also up for good news and ready to rename his organisation the Wapiti and Moose Foundation — just as soon as he sees a photo.

‘‘Ken is very honest and not out for a story. If the DNA evidence wasn’t moose, what else could it be?’’

Meanwhile, Mr Tustin is still smiling broadly at the recent sightings and a lifetime of fun in the forest with a woman he loves.

He also cherishes the friendships made along the way.

‘‘It means the world that smart, observant people have been so lucky to have their tracks crossed by this rare, rare animal and recognise the importance and want to share it. We are thrilled for them and ourselves.’’

‘‘They have brought the project back to life, just when we’ve been struggling to do the fieldwork, and when moose numbers are at their likely lowest ebb.’’

‘‘It’s something to celebrate in this mean old world of ours. A flash of bright light. I love it that when man believes he knows everything, then here comes moose, unheralded, the size of a horse, outwitting — or outmoosing? — us all for years. What does that tell us about ourselves and the quality of Fiordland wilderness? Moose 1, humans 0.’’