It is a long journey from Kirkuk to Timaru, as Rotary Timaru’s newest member knows.

Ari Jan, who works to resettle former refugees into the the area, has a personal knowledge of the pain displacement causes.

Thirty years ago, Mr Jan and his parents and a sister moved to New Zealand after a decade in a refugee camp in Syria.

Mr Jan was born in Kurdistan, the sixth child of seven.

When people heard his accent, many asked him where he was from.

His response was often followed by ‘‘Where is that?’’

While replying with ‘‘Iraq’’ might simplify things geographically, it was an offence to the young boy who was chased from his own country by gunfire.

Kurds came from the rugged, mountainous regions of the Middle East, particularly in the areas of modern-day Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

While they were the indigenous people to the area, over time they had been the target of prejudice and — at times — persecution.

His own childhood was amid Saddam Hussein’s Anfal regime, which was described by human rights groups as a genocide against the Kurdish people.

He could still remember waking up one morning and discovering his mother was gone. She was one of many people taken from the area during the night.

His father told him and his little sister the government had taken her for a while, but he would find a way to bring her home.

Mr Jan discovered later that his oldest brother had become involved in politics, and had joined the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), who were freedom fighters.

His dad reminded them not to talk to anyone outside the house about his brother, even at school, as it was how the government found people.

Those repeated warnings paid off.

He said some time after, he was escorted from his classroom by a man with a gun and driven away in a government intelligence car.

No-one at the school protected him.

While he was being interrogated, his mouth and lips were dry from fear.

‘‘I started crying and said I did not know anything.’’

But the interrogation continued.

If it were not for an older man leaving a strategic door unlocked for him to escape, Mr Jan had no idea what might have happened to him.

When he returned home his father took him and his sister to live with their older sister in a different city.

He said his father did not stay with them, as he was determined to search for their mother.

Mr Jan said loss was such a simple word, and it did not capture the depth of what the family experienced.

He had sacrificed his education so the government would not find him, his mother was missing, his father had gone to search for her, and he had lost his childhood home and all his possessions.

Mr Jan said he and his sister were not finding it easy living in hiding.

After about a year in jail, his mother was driven in a truck and thrown out near the border to Iran.

She was told to leave her country without looking back, or she would be shot.

She walked until she reached a safe village, but was desperate to return to find her children.

Everyone she met tried to persuade her not to, in case she was found and executed.

‘‘One night she started walking.’’

When she finally reached a relative’s house they hid her there, and sent a message to the children.

‘‘As soon as my mother saw us, she burst into tears.’’

She held her two youngest children all night.

He said her year of torture and interrogation had left its mark; her health had deteriorated and her head shook permanently.

Later, during the Gulf War, the United States of America (US) and its allies supported the Kurdish people to rise up against the regime, but the regime regrouped its forces and attacked, causing more than 1.5 million Kurds to flee to Iran and Turkey.

He and his family were among those numbers, they walked for a week to get to the border, drinking rainwater on the ground in desperation.

One memory of a young boy would haunt him.

‘‘In the chaos of escaping shelling and bombardment, I noticed him from 100 feet away, lying on his stomach.’’

Mr Jan thought the boy was tired and hungry from walking, and wanted to fall asleep.

Despite his fear of being shot, he went to check if the boy was all right.

He sat with that wounded 9-year-old boy until the boy’s last breath.

When the conflict settled, people returned to their homes but Mr Jan’s family had nothing to return to.

Instead, they relocated to a refugee camp in Syria.

His family spent almost a decade in the camp, witnessing the bare land evolve from a village of tents to a large village of homes built from the earth.

Different people arrived, too.

First there were the Yazidis, Kurds and Arabs, and later Somalis.

While the different cultures had different sections of the camp, he said they all got along like a big family.

They understood each other’s pain without saying anything.

Mr Jan said nowadays the camp served as a detention centre, and was full of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) members.

He sometimes wondered which jihadist militants were living in the house he and his family built.

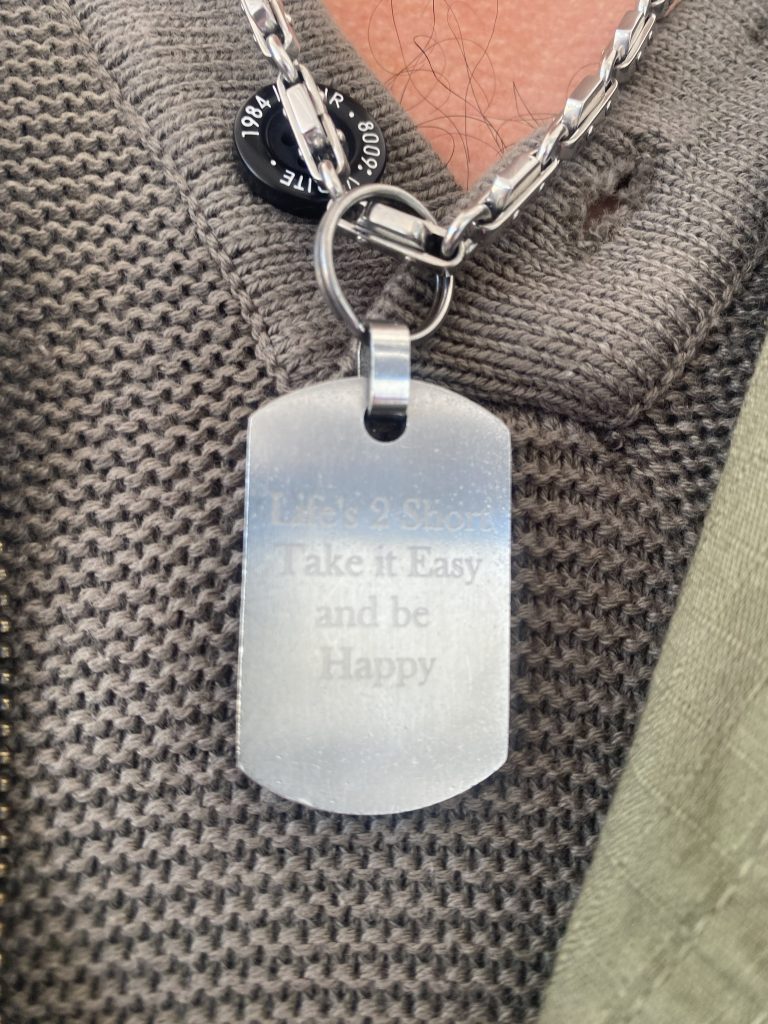

Mr Jan said he was still hurting, but New Zealand had offered him the privilege of not only embracing his Kurdish identity but also sharing it with a wider community eager to learn about it.

‘‘Some times people ask me, ‘You don’t miss home?’ and I tell them this is my home.

‘‘I want to live in peace.’’